Archive

THE RETURN by Donald Mahler

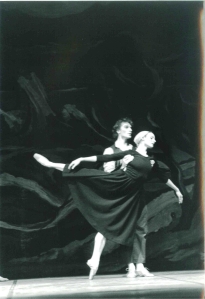

Jardin Aux Lilas, 2012 - Ballet du Rhin. L-Alexandre Van Hoorde. R-Christelle Daujean-Molard. Photo: Jean Luc Tanghe

Some twenty years ago my telephone started to ring. This ringing proved to be the harbinger of something which actually changed my life in a very big and entirely unexpected way.

Sally Bliss had a proposal for me. A request by a company in France for Dark Elegies had come in. Because both of the Tudor Trust’s Répétiteurs Sally Wilson and Airi Hynninen were already engaged and unavailable, would I go over and stage it? Well, would is not could!!

I had up until that time not staged any of Tudor’s works. Over the years, I had danced in a number of them – principal roles in Jardin Aux Lilas (Lilac Garden), Offenbach in the Underworld, Echoing of Trumpets and lesser parts in Dark Elegies and Gala Performance. But all this, plus years of watching performances, many with the finest Tudor interpreters, including the great man himself, did not automatically give me the ability to stage these masterpieces. To be an honest player in this time honored profession, I felt that I needed to have a great deal more knowledge of these works than I had. Even to coach these works requires much more than a passing acquaintance with them. “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” That is what I believed then and honestly, what I still believe.

So, my answer to Sally’s proposal was a strong no. Sally, being the ever positive person she is, wouldn’t take no for an answer and phoned me for a second time with a variation on her theme. If she sent a notator to actually teach the “steps,” would I then agree to go there and coach the ballet? The notator would go there for two weeks and then, after she left I would arrive and continue the work. With much trepidation, knowing that I would be working on my own, I at length, agreed to this proposal.

This agreement changed the course of my life. First, I set to work with Sally Wilson to try to fill in what I did not know. Then, working with the dancers on what the notator had already set, I had to correct numerous errors and develop the inner meaning and intent of the choreography, a massive task and a responsibility which I did not take lightly! As things turned out, eventually, I wound up staging the entire 5th Song on my own. This process, working together with my own memories and experience, enabled me to start with small baby steps down the road along which I have traveled ever since.

I arrived in the small town of Mulhouse to begin working with Ballet du Rhin on Dark Elegies. I immediately fell in love with the company. They were basically classically trained with a very interesting repertoire. On the same program and rehearsing at the same time as I, was Anna Markard, the daughter of the famous German choreographer, Kurt Joos. She was staging his masterpiece, The Green Table.

What a wonderful experience! Two of the most historic and artistically important dance works in the Dance Repertoire! Both created in the 1930’s in Europe and still pertinent and being performed then and today! The dancers took to Tudor’s work right away and happily, to me as well, with great warmth and friendship. They helped me to enter into the process and overcome my self doubts. There was a great deal of work to be done. My efforts to really learn the ballet proved to be the correct way to go and over the course of time, bore fruit. The period spent with these dancers turned out to be a wonderful learning experience both for me and for them. That my relationship with this company and with Tudor’s ballets would be unexpectedly prolonged was beyond my imagining and yet, due to the success of the performance, I was asked back the next year to stage Jardin Aux Lilas.

The return to a company is always a much sought after experience for me. I will have become familiar with the dancers and they will have gotten to know me. More importantly, they will have become familiar with what Tudor’s work is about and with the qualities he asks for. Jardin is however, very different from Dark Elegies. The ability to become a dancer-actor was a big transition for them. The dancers were also puzzled by the music. Its lush romanticism was not at all like the stark music of Mahler. Some time after we had been working on Jardin, one of the dancers told me that, when they first heard the Chausson they hated it. But, after learning the choreography they began to appreciate and even love the music and that was so because of the ballet!

Eventually all this came to an end. Friendly relations became lovely memories. Our lives drifted, as is only natural, apart. Yet, these two productions with Ballet du Rhin were terribly important for me – the start of a wonderful voyage of discovery.

Now, after 20 years of working on Tudor’s works with companies around the world and feeling pretty worn out at that, in a repeat of the past, the phone rang. There was Sally’s voice on the other end. She said that a company in France wanted to do Jardin Aux Lilas and had asked for me to stage it. Which company? Ballet du Rhin! Twenty years later and a return to the place where all this began! How amazing!

In the years which had passed, much of Mulhouse had changed. And yet much had not. Still there were the wonderful old buildings. Still there was the town square with its Cathedral. Now all was bustling with Christmas decorations. Many stalls had been erected with things to eat. Crepes!! Things to drink and lots of noise. Even a giant Ferris wheel. All very reminiscent of the fair in Petrouchka. I set out to find the Theater where the studios are located. Unbelievably, my feet seemed to know where to go and without any difficulty, there I was.

Inside, I found, standing in the office, old friends from my first time with the company. Claude Agrafiel who had danced Caroline and the First Song in Dark Elegies and who is now Ballet Mistress, and Didier Merle who was Ballet Master then and who is Ballet Master now and with whom I was slated to work once again on Jardin. With joy we immediately recognized each other after all these years! During the time I was in Mulhouse, a number of the dancers who worked with me in my first time with Ballet de Ruin also came by to visit. It was a great pleasure to see them.

The company now is much the same as before. A different Director, Bertrand d’At, has brought in a more or less contemporary repertoire but with strictly classical training. A strong sense of musicality and very fluid movement was very much in evidence. I was incredibly impressed by their work ethic. I watched many rehearsals and never saw anyone mark or give less than 100% of themselves – and all in a happy atmosphere! Even with me!

Rehearsals were interrupted by an 11-day Christmas and New Year’s vacation. When we all returned I found them in the studio before rehearsals started, going over, on their own, what we had done before the holidays and helping each other to work things out!

I was so thankful for their patience with me. My weird sense of humor and the geriatric nature of my “demonstrating” must have been more than they bargained for! I am grateful also to Didier for his help and friendship. What a lovely way to work! I also want to express my deep gratitude to Bertrand for his support and for sharing so much of his time.

Surely there must have been conflicts there. All companies have them. It is just that I didn’t ever see evidence of them during rehearsals. I was enormously impressed and moved by their warmth and openness with me.

These qualities were strongly in evidence by the way they interacted with their children. Yes, I said children. There are many couples in the company, both married and otherwise. Parents to a raft of children! The loving and caring way they were with them was indicative of their qualities as artists. I cannot find the words to express how impressed I was by the maturity of these dancers, so well developed as people in their attitude towards life and towards each other. Mr. Tudor, who looked for dancers to be people rather than dancers, would have loved this company – but not more than I do.

Sadly, this is to be Bertrand’s last season. A new Artistic Director has been appointed to take over the leadership from him. I wish for him, and the company, continued success and happiness in the future.

VIEW SLIDESHOW OF ADDITIONAL COMPANY PHOTOS BELOW…

ACTING FOR THE DANCER by Hilary Harper-Wilcoxen

Shut out — unable to buy a ticket to the Paris Opera’s performance of Othello because it was sold out; an opera! — like a rock concert in the States. I doubted whether too many operas were ever sold out back home; maybe at the Met . . . maybe not.

So why did I care? I had plenty to keep me busy while in Paris, but I was truly disappointed at not being able to see Othello, and I’m not even that big an opera fan. The answer was obvious: Othello is a great story, told by a master. I had recently seen the original Shakespeare version directed by that most quixotic and surprising of theatre/opera directors, Peter Sellars. I had loved it. Iago stayed with me, as did Desdemona. That’s my personal test of great theatre; does it change me while I’m at the theatre and, then, most important of all, does it stick with me months after — that performance had. So, what had made it so powerful? And then it hit me: the subtlety and complexity of Shakespeare’s Othello derives from the fact that his characters are human; they are rich, contradictory and layered; we can relate to them on a very personal level.

This is not an article on Shakespeare, it is an article on ballet and ballet dancers. In this essay I will make the case for actor training for ballet dancers. I will use examples from Antony Tudor’s work and my teaching experience and suggest that teaching ballet dancers to be strong actors is both necessary and teachable.

Back to Shakespeare. Here’s the connection: when ballet enables us to empathize fully with the characters we are watching we leave better for it; changed, challenged. However, and this is where the two diverge, when it is solely about beautiful bodies doing amazing things in fabulous costumes we do not necessarily leave with, as dance historian Judith Bennehum puts it, “ a heightened sense of who we are and what we represent”. This is a critical point, and one which I believe is often overlooked.

Ballet is many things to many people. For me, it is a way to communicate without the need for speech; to find freedom through its seeming opposite — dedication and discipline; to approach universal ideals of beauty, control and grace. It is also a unique opportunity to engage others in thinking about the human condition, if approached with that intention. Unfortunately, it rarely is. Most ballets lack the emotional depth of Shakespeare; they are more interested in technique and less in character development. This should come as no surprise, given ballet’s origins when the importance of display and elegance often took precedence over the intrinsic potential of the art form. Of course, ballet has come a long way since Catherine de Medici and the court of the Sun King; but we can go further.

In the world of ballet, the 20th century English choreographer Antony Tudor stands out as a shining example of a choreographer who went further, who got what Shakespeare was after: the turmoil and transcendent possibilities of the human condition; the inevitable consequences of both duty and selfishness, hope and despair. Tudor brought real people to the stage through his characters, and had them reveal their inner lives to us, the audience, through the unlikely medium of classical ballet. Whether the ballet is about a forced marriage in Edwardian England (Jardin aux Lilas) or heinous war crimes during the German occupation in WWII (Echoing of Trumpets), we care about the story that is unfolding, care about the individual lives it reveals. Tudor accomplished what all great artists seek to accomplish: to make the story unfolding on stage relevant to the audience; to have them respond to the universal truths, trials, and triumphs which define each one of us.

Tudor was also a master of comedy. Another mark of greatness for, through humour, we also find truth; often more easily, though not always less painfully. His comedies were poignant, sardonic peeks at the less glamorous side of things. From the ironic characterizations of diva ballerinas in Gala Performance to the somewhat pathetic attempts at seduction in Judgment of Paris he saw with a laser-like eye what comedy always looks for– the asymmetry of life, the contradictions and the touching nuances . . . the unexpected.

So where does all this take us? Although Tudor died in 1987 his work is consistently presented in such companies as American Ballet Theatre and throughout the world. He continues to be considered the “Stanislavsky of ballet “ a reference to the great Russian actor who founded the technique associated with honest gesture and powerful character development. His musicality (The Leaves are Fading) and complex narrative (Pillar of Fire) are still stunning examples of a great artist’s work within the ballet genre. But his reputation is transient, as is so often the case in dance. Unlike the master works of visual artists, musicians and writers, ballets are quickly lost if not painstakingly videotaped and notated. The Antony Tudor Ballet Trust is doing an extraordinary job of preserving and sharing Tudor’s masterpieces under the energetic and visionary direction of Sally Brayley Bliss. This work is critical in large part because of Tudor’s masterly use of character. He is considered the Proust of ballet because of the strong development of narrative and character that identifies every masterpiece we know as “Tudor’s”.

By contrast, many classical ballets use the characters involved as a way to move the plot along; to serve as scaffolding for the choreography. They don’t really matter, they simply exist as tools, not as people.

On the other hand, Tudor has characters as real and tormented as any Lady Macbeth or Iago in almost every one of his dramatic ballets. Because of this ‘playwright-esque’ ability to create powerful characters within ballet choreography Tudor deserves to be studied in the same way as an art student studies (and copies) Rembrandt, or a music student Beethoven, or a theatre student, that’s right, Shakespeare. As it turns out, Mr. Tudor is the perfect choreographer for college and university dance programs because of his proclivity towards delving into deep, sociologically rich themes. For him it was not simply about technique or entertainment; it was about meaning. He meant for us to care about his narrative line, not simply follow it. It is the stuff of great literature, music and art — all of which he loved. It is still hard to define exactly where Tudor fits in today’s world of classical ballet, but he does clearly belong there; if nothing else, as an example of how it can be done . . . how it was done.

My personal experience with Mr. Tudor goes back to my childhood. My mother studied with him both at Jacob’s Pillow and at the Metropolitan in NYC. She had been a theatre major in college and came to ballet quite late for a dancer. For exactly these reasons, Mr. Tudor was the perfect teacher for her. I grew up hearing stories about how he would single her out during class and say, “Now everyone, watch Trude run, she actually looks like she’s going somewhere! That’s what I want.” That interest in honest movement (movement that had a motivation and a need) was quintessential Tudor.

Today’s dancers need that kind of attention to detail and motivation as much now as they did then. In our “continuous partial attention” 1 culture we can hardly wonder that our dancers seem lost when we ask them to fully engage in the moment . . . in one moment, not four scattered, disparate moments of multi-tasking-communication. The building blocks for powerfully projecting character on stage have not changed: To be fully in the moment; to be both kinesthetically and emotionally aware of your surroundings; to find honest gesture. These are skills I find are sorely lacking in most dancers these days. But they are skills, not gifts from above and, as such, I believe they can be learned.

The lack of artistry or the inability to embody a character as a dancer, are common complaints among many dance professionals. As a dance professor at Principia College (a small Midwestern, liberal arts college) I teach theatre movement, as well as dance, to both actors and dancers. I have observed this need for what I will call “artistry” first hand. I have also observed how it can be addressed, specifically for ballet dancers, but it can extend to all dancers. I believe that Antony Tudor’s oeuvre and legacy has much to teach us, and that exploring his work can bring illumination to the training of today’s dancers (and future choreographers); to make them artists, rather than simply athletes. I also believe, and have experienced this in my classes, that a combination of Laban Movement Analysis, Bartenieff Fundamentals, good old-fashioned Stanislavsky intention work and small doses of Alexander alignment can also work wonders.

For the last three summers I have had the privilege of guest teaching at L’Academie Americaine de Danse de Paris in the peaceful residential 16th arr. It has been a transformative experience as an artist/educator mainly because the Director, Brooke Desnoës, has allowed me autonomy in teaching the four week International Summer Intensive dancers in my “Acting for the Dancer” classes. Our philosophies for teaching dance are eerily similar. In her own words, “Respect, honesty and hard work are at the centre of everything we do. Classes are kept small and instructors get to know each student individually, in turn students are provided with encouragement and confidence to challenge themselves in new artistic ways.”

Part of my guest teaching while at AADP included a traditional ballet class; this has enabled me to experiment with how best to coordinate the two so that the students learn in a circular pattern. The last two summers I introduced Laban’s eight effort actions, some Bartenieff Fundamentals and a few Alexander exercises. We did some character work with the Laban effort actions (i.e. wring, press and float to name a few), as I do with my theatre movement students. I also had the dancers do some work outside the classroom — observing gesture and movement in strangers. This year, however, was the breakthrough.

Having worked all year with the Tudor Trust Committee on the innovative Antony Tudor Dance Studies Curriculum for Colleges and Universities headed up by Sally Bliss, I was more fully aware of some aspects of Tudor’s work that I had not fully appreciated before. For one thing; his fascination with dancers who could embody their role was a defining factor in his process. This took me back to Tudor’s roots: he trained as an actor before he ever trained as a ballet dancer, and he studied music from a very young age. Therefore, I gave my dance students a scenario in which to work; something all actors are well acquainted with. We were not working with actual Tudor choreography as I am not a Tudor repetiteur, and, anyway, I wanted them to find honest gesture on their own to begin with . . . to realize what that meant and how it felt; not an easy task for most ballet dancers. Based on the concept that their movements should have meaning, should express something about the character they had chosen for themselves, I asked them to come up with pedestrian movement that was real. They were given a beginning, middle and end point, and a partner, but that was all. This autonomy enabled them to have some ownership of the process, a key component in higher modes of learning. They also had to find a reason for their movement. I kept reminding them of the Tudor “mantra” which is to let the movement do the communicating and the facial expressions and other needed expression will follow. I had showed them excerpts from Jardin aux Lilas at the beginning of our time together and I kept referencing what they had seen, and playing bits of it again (specifically the opening scene) for clarification. They were not to recreate it, but to use it in their own work of creating honest gesture.

They quickly learned to open up, to become less concerned with “getting it right” and more concerned with just doing it wholeheartedly. I explained that that sort of approach inevitably leads to honesty, as it is inherently honest. As one student who had trouble finding expression in her dancing put it, “I learned that I must immerse my whole self and go past the point at which I feel “comfortable”.”2

The final two days of classes included a scenario which I choreographed for them. The scenario follows:

You are alone in a forest, sleeping; a noise wakes you; you get up and look for what it might have been. While searching you are startled by another noise; you slowly move away but are drawn back to see if you can discover what it was; you do, and flee in horror, exiting stage left.

I introduced this scenario in stages, giving some of the steps in technique class earlier on and then incorporating them into the final 72 count phrase. Repetition was critical as dancers are so accustomed to it, and especially need it when trying something new like this. Some of the comments from the group of older dancers with whom I worked the most are included below:

From a French student: “Il faut effectuer les gestes sur scene sans les anticiper” or “You must not anticipate your gestures on stage.” 3 This idea of not anticipating what you know is coming is critical for honest responses on stage (sur scene). It is also very difficult and requires the dancer to understand and be able to recreate, time and again, the ability to be “in the moment” — a concept that seems harder for dancers to grasp than it is for actors. Perhaps it’s because, as my mentor in theatre movement Margaret Eginton from Asolo Conservatory explains, “dancers speak with steps and so need more in the moment preparation of their instrument

Another important piece of this puzzle is how dancers approach the work itself. They are typically uncomfortable with “acting”. . . and rightly so. To be told to “Look happy now” or, “You need to look scared here” is very unnatural for dancers. They have been trained to do the steps well and to listen to the music, but mostly so that they will be on the beat with the others on stage; not as a catalyst for emotion. To graft onto a difficult combination of steps a feeling is hard for them and usually turns out badly; as I often say in class, “That was fake”. We worked a lot with this issue right from the start. One of my students from the intensive puts it far better than I could:

“I was never presented with the opportunity to be a character so fully that I truly felt I was that person. It is a completely different world. Your exercises present dancers with a difficult challenge that is as much about self exploration as it is about discovering different characters. …I tried to embody the music. We learned to constantly dance in the moment and to observe those around us in order to comprehend the meaning or emotion behind a certain gesture.” 4

As Desnoës puts it, “ “Incorporating “Acting for the Dancer” classes into the summer curriculum has helped the young dancers to get ever so close to that artistic freedom experienced when one “becomes” a character. It is delightful to watch their faces when they are able to feel that for the first time. I am certain that this connection between dance and feeling the character remains with them as they continue their dance studies and, more importantly, kindles the artistic process inside them.”

That “artistic process” is really what this work is all about. It has a lot to do with both discovering how to become a character and to embody the music, that elusive element that was also a key concept throughout their training. To really hear and feel the music, not just count it is something of an anomaly for many dancers today. Like the character work, however, it can be learned. Many times I have found that all a dancer needs is explicit permission to “let the music move you” from the choreographer or teacher and they are eager to do so. All of the dancers found a road they could travel to find expressive gesture and honest movement . . . my basic goals for the class.

Antony Tudor is not the only ballet choreographer who has ever worked to find honesty in movement; but using Mr. Tudor’s works as an example of where this can be found in classical ballet has been most helpful. For today’s college dancer the use of various techniques to achieve this end seems both logical and in tune with the ideals of a liberal arts education. In exploring these paths some of them came from reading or hearing about exercises Mr. Tudor had used in his technique classes; some I observed while Tudor repetiteurs Amanda McKerrow and John Gardner worked with my dancers at Principia College. Other ideas came from Margaret Eginton’s coaching and observing her classes and my graduate work on my MFA where my thesis was on how to incorporate Laban Movement Analysis in my work with actors and dancers. Years of teaching theatre movement, choreographing and teaching ballet have also informed this practice and lead me in new and different ways.

The overarching goal of training more artistic dancers through giving them a way to find expressive gesture is ongoing. In this age, dancers in university programs need to have both a goal and a map: the goal is to be able to fully express any character they may be asked to embody through their movement. The map is a clearly articulated yet flexible set of exercises and approaches that enable the dancer to arrive at honest gesture and let go of self-imposed limitations and fears. I don’t know if Mr. Tudor would be pleased if we reached this goal, but I know I would.

- “Does America Have ADD?,” U.S. News and World Report, March 26,2001, 24.

- Camille Kemache at AADP workshop, summer 2011, Paris, France

- Fanny Serenque at AADP workshop, summer 2011, Paris, France

- Mikkailla Bolotenko at AADP workshop, summer 2011, Paris, France

SALLY BLISS KEYNOTE CORPS DE BALLET INTERNATIONAL – JUNE 22, 2011

This speech is how my life, from very humble beginnings in Halifax, NS, Canada became interwoven with one of the great master choreographers of the 20th Century.

Antony Tudor: …my mother mentioned his name to me when I was a dance student, approximately ten years old. My teachers were Latvian immigrants. They were Russian trained and certainly had never heard of him.

Tudor was an important choreographer in my mother’s world. I don’t know why she knew about him, but she was a true Balletomane, the name for lovers of Ballet in those days. But she knew all about his ballets: Lilac Garden, Dark Elegies, and more. At that time in Canada, Celia Franca, a former dancer with The Rambert Ballet during Tudor’s time there who then went on to dance with The Royal Ballet, formerly called Sadler’s Wells Ballet, was brought to Canada to found a National Ballet.

Celia had worked with Tudor and danced in his ballets at Rambert. She revered him. Upon founding the NBC, besides the classical repertoire, she brought in four Tudor works: Lilac Garden, Dark Elegies, Gala Performance, and Offenbach in the Underworld, a work he created for a small company in Philadelphia. Resetting it for Canada he developed and refined the work and it became an established ballet in NBC’s repertoire.

I joined the company and had the honor of dancing in 3 of those 4 ballets in the repertoire at that time. My mother was to me amazing, having known of him from when he first arrived in the U.S., and opening my mind to this great choreographer, was pretty special.

How interesting a young dancer, born in London, living in Nova Scotia, Canada in the late 40s, early 50s, by a twist of fate, meets this great chorographer of the 20th century; and how my life connected with him throughout my career! He is the Godfather of my eldest son, Mark, and I have been given the task of sustaining his legacy for future generations of dancers.

I had six great years with NBC and decided I really wanted to move to NY to study. I did visit New York before moving and I remember my first class with Tudor: I stood in the back, hoping to hide, then I heard “Hey, Maple Leaf Forever, come up here!” I was petrified! How he knew I was from Canada so quickly I’ll never know.

I moved to New York in 1962 and was accepted as a dancer into the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. At that time the new the Director of the Ballet, was Dame Alicia Markova, whom I loved. She was funny, respectful, taught a terrible ballet class, but that was ok because we had most of our classes with Antony Tudor and Margaret Craske.

I had the honor of dancing the Prelude from Les Sylphides with her coaching was me. Remarkably, Les Sylphides was the very first ballet I saw at age 5. Markova was dancing the same prelude, and here she was twenty years later coaching me in that same part. Markova was a great friend of, guess who… ? Antony Tudor, who created the role of Juliet in his magnificent Romeo & Juliet for her.

Markova created “Ballet Evenings” for the Metropolitan Opera Ballet and they were creative with major ballets. Our first evening was Les Sylphides, then small works such as Dolin’s Pas de Quartre, Petipa’s Rose Adagio, and we closed with Folkine’s Scheherazade. But the third ballet evening was very exciting. Markova convinced Tudor to do the American premiere of his work Echoing of Trumpets that he created on the Royal Swedish Ballet. But best of all she somehow convinced him to create a brand new work on us. It was called Concerning Oracles and the evening ballet closed with Bournonville’s ballet, La Ventana.

This was maybe highlight of my life. I was cast in both the Tudor ballets and La Ventana, and not only that, he had me learn every part in both ballets, except the little girl in Trumpets (I was 5’8”, and not a little girl type…). For at least eight weeks we worked with him around the clock. We would stop only to dance in the Opera Ballets, come off stage, and go to work until midnight (no unions at that time). Can you imagine what an incredibly exciting learning experience this was for all of us? This period is still in my memory. In the end I danced the tough woman in Echoing of Trumpets, and an incredible pas de deux in Concerning Oracles. In the last scene, Lance Westergard was a young boy; we were a family picnicking in a French garden. I was an old, dowdy aunt and for some odd reason Lance dreamt of me as a sexy lady. I stripped down from my dowdy clothes to a frilly, pink peignoir and we danced this pas de deux which kept building, and every time the audience was expecting Lance to lift me, I lifted him. He was 5’5” and I was 5’8”. It was hilarious and actually brought the house down. Lance and I were totally in the dark while learning it. We had no idea it was funny. Imagine having a ballet by Antony Tudor created on you?

During my tenure at the Met, there were highlights and lowlights: Franco Zeffirelli took me up to wardrobe and designed my costume for the opening night of the new Met’s Anthony & Cleopatra, with choreography by Alvin Ailey.

In the ballet in the Opera La Pericole, I was dancing the lead, and the English actor, Cyril Richard, playing a comedic role, joined me in a partnered cartwheel at the ballet’s end; and, somehow he ended up on top of me, flat out, my tutu over my head. We looked at each other and with no music, got up, did it again perfectly.

The second opening of the new Met was La Giaconda. It’s a long story, but my partner drank himself into oblivion and dropped me on every lift – a disaster – a moment I will never forget. It’s funny now….

It was around this time I married Anthony Bliss and felt it important for me to leave the Met. Tudor was about to restage Echoing of Trumpets for Ballet Theatre and convinced Lucia Chase to take me into the company, and I danced the same role – the tough woman.

After one season, which was again a great experience, Robert Joffrey asked me to join his company to dance the leads in six ballets. His Pas des desses, Taglioni, Arpino’s Viva Vilvaldi and Elegy, and Ruthanna Boris’s Cakewalk in the part of Venus, Balanchine’s Scotch Symphony, and Lew Christianson’s Jinx. I couldn’t resist the offer and so accepted the invitation. I danced the season five months pregnant with my 1st son.

Under Robert Joffrey’s direction, I danced two seasons with NYCO as leading dancer in Joffrey’s Manon & Arabella, Frank Cosaro’s Trovatori and Prince Igor with Edward Villella. (I can’t remember for the life of me who choreographed…).

At that time the great dance educator, Lillian Moore, retired and Robert Joffrey asked Jonathan Watts and me (both of had just retired) to take over the apprentice program at The Joffrey School. This turned into a very productive second company, The Joffrey II Dancers. Jonathan left and for the next 15 years I developed a successful company of emerging dancers, choreographers, designers, composers and administrators. We did a number of Tudor ballets coached by Tudor himself. We commissioned five new works a year, which we produced, and we did ballets by Joffrey and Arpino. We toured many months of the year and many alumni went on to great success: Eileen Brady, Billy Forsythe, Choo San Goh, Tina La Blanc, Elizabeth Parkinson, Glen Edgerton, to name but a few..

During the beginning of the 80s, I went down to the Joffrey School to pick new dancers (Bob had taken about eight of my 12). I was intrigued by this young boy who jumped like an antelope. He was very green but I liked him. After I picked him I found out he was Ronald Reagan’s son, Ron. That was a trip. We lived through the campaign, secret service, the inauguration, Ron’s elopement, and the shooting of the President. Ironically, we were on tour in “Lincoln” Nebraska the day it happened. Ron went on to the 1st company and did well, but left for a more lucrative career in the media.

During this time I was on the board of NARB, later and now called RDA, where I adjudicated festivals – 2 in the PNW, one S.E., one N.E. and the mid-states for the 1st national conference. I also taught at many of these festivals. These festivals were a very important part of the development of dance in America.

After these fifteen years, it was time for me to move on. I continued teaching, advising, consulting, and making speeches, and my first love, encouraging young dancers and choreographers to continue in their profession.

In 1987 I was appointed by President Reagan to be a member of the National Council on the Arts for six years: we were the Board of Directors for the NEA. It was very hard work and a fragile time. The right-wing wanted to do away with government funding for the Arts. Jesse Helms was the outspoken hero for the right. It was so stressful. To be honest, with a lot of hard work the Endowments does still exist, but it remains tenuous. That whole experience could be a speech on its own. If nothing else, I learned one hell of a lot. I’m honored to have been there but it was probably one of the most difficult experiences of my life.

My mentors, Antony Tudor, died in the spring of 1987; Alvin Ailey, died in 1988, and Robert Joffrey died in 1989; and my husband and father died in 1991, within a week of each other. This time was sad for me, but it was a busy time and probably good.

Upon Tudor’s death, I was appointed co-executor of his Estate, and named sole Trustee of his ballets, which became The Antony Tudor Ballet Trust. This entails that his ballets are staged and performed as near to his expectations as possible. I have répétiteurs who stage his works all over the world.

It is my mantra to make sure Tudor’s ballets are seen worldwide and never lose their artistic integrity. His ballets are not about steps; they are about nuance, gesture, soul, quality of movement, and musicality. The Trust has excellent répétiteurs, many of whom worked with Tudor when he was staging, creating and coaching.

We held a centennial conference at Juilliard, Lincoln Center, New York in 2008. We had approximately 300 attendees. It was very successful with Tudor classes, taught by former Tudor students; panel discussions with Tudor dancers and with writers and musicians; workshop performances of four of his works : excerpts of Undertow, Juilliard; Little Improvisations, JKO School; Continuo, ABT II; and Judgment of Paris, New York Theatre Ballet. We had a wonderful reception for everyone to get together, which culminated in a performance by the Juilliard students in his great masterpiece, Dark Elegies. Maybe most special were the remembrances which we videotaped with each attendee, their thoughts and memories, many of which brought tears to our eyes; as did the remembrances of Tudor’s relatives, who traveled all the way from New Zealand to our event.

Out of this we have created a video of the event, and best of all a book. If you are interested, we have them for sale on our website http://antonytudor.org/store.html. The proceeds for the sale of this book and DVD will fund an endowed scholarship in Tudor’s name at Juilliard.

We are at this time developing and launching The Antony Tudor Dance Studies Curriculum for college and university dance programs. We will discuss this tomorrow.

In 1995 I was asked to be Executive Director of Dance St. Louis, one of the few dance only presenters in the country. We started a unique educational program throughout the state. We raised funds to bring all kinds of dance to St. Louis, the best in every field: Rennee Harris, HipHop; ABT, full length Romeo & Juliet; Nacho Duardo’s company from Madrid; Paul Taylor; Hubbard Street; San Francisco Ballet; The National Ballet of Mexico; Tango Times II; Groupo Corpo, Brazil; Sydney Dance Theatre; Miami City Ballet; Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre; Mark Morris; and Pibololus. We brought these companies back many times during my tenure, and through this work we developed a very intelligent dance audience. They know what’s good and bad. I’m proud of this legacy. What is really important is that there is dance audience out there – east coast, west coast and mid-states.

Before I close, I’ve had the honor of serving on many Boards including: The Board of The Joffrey Ballet; Chairman of the Board of Visitors of the North Carolina School of the Arts; Board of Trustees of New England College, Henniker, New Hampshire; Advisory Board of the Kathryn and Gilbert Miller Health Institute for Performing Artists; The Dance USA Board, and The Paul Taylor Dance Company, among others. I’ve been thrilled to receive many wonderful national and local awards as well.

Antony Tudor has been the thread throughout our life in dance. Are we lucky? Yes! Are we finished? No! There is always so much more to do. This is my “Examining of Tradition and Innovation” throughout our careers, and Antony Tudor is the legacy. We want his legacy to continue forever. He was a genius and he must not be forgotten.

###

Paula Weber, CORPS de Ballet President on Tudor Curriculum

What most intrigues you about Tudor’s teachings? His incredible insight to human emotion and the way Tudor conveys this in his dances. He knew how to touch the soul both in tragedy and comedy. His ballets are timeless. It is absolutely imperative that these works are never lost!!

Why is an Antony Tudor Dance Studies Curriculum necessary? I feel that in today’s social media world we all spend a large amount of time in front of a screen – especially our young people who are so “connected.” I find it hard to reach the emotional quality that is so important for dance/dancers. Their eyes seem to have that glazed over “computer screen” look. Perhaps by studying the master of emotional sense through the Tudor Curriculum, students can bring heart back to their work by getting in touch with the most important part of dance – personal connection, personal feeling, the personal communication that happens between a dancer and the audience.

Accreditation ensures that the education provided by institutions of higher learning meets acceptable levels of quality. How will the conference further that purpose? The beauty of the CORPS de Ballet International Conference is the interaction of a membership of 90+ dance professors and representatives of approximately 50 colleges, universities and professional schools. It is our time for renewal, recharging, networking, and learning. Those attending the conference will learn directly about the Antony Tudor Dance Studies Curriculum and have the wonderful opportunity to work directly with Sally Brayley Bliss and the committee of scholars and répétiteurs. Even those members who don’t attend the conference will have the opportunity to learn about the curriculum through the CORPS website and the members’ forum. The knowledge we gain by this opportunity will be shared with our students and open doors for the Tudor curriculum group to have residencies at many of our schools. Exposing our dance students to the teachings of Antony Tudor is not only an historical experience, but also a rare dance training experience – Tudor was a master, and as with all great works projects, the intellectual growth and exposure to the artistry of the masters vastly enhances the education of our students. This exposure to such art is the quality of education that is absolutely essential as it fosters discovery, creativity and learning of the highest caliber.

What are the advantages to artist-in-residency programs for students, as opposed to summer institutes to train trainers, for example, or other methods of delivery? I feel artist-in-residency programs are far more intensive to learning the art of dance. They are more one-on-one, more in-depth. The passing of knowledge becomes more multi-dimensional and detailed. The experience is highly specialized, creating strong foundations of discipline and craft.

What evaluations do you use to assess the success of existing dance curriculums? I feel assessment is judged by the success of our students upon graduation, and determined by what we bring to students during their four years of study with us – the curriculum (dance training, dance academics, general/specialized academics), performance opportunity, professional performance opportunity while in school, exposure to the masters and great works projects, residency projects and guest artist projects. Our degree is a BFA in performance and choreography.

Paula Weber is Chair of the Dance Division and a professor of dance with UMKC’s Conservatory of Music and Dance.

Agnes de Mille’s Eulogy for Antony Tudor

AGNES DE MILLE (1905-1993)

This is a sad day for us. It’s a cruel day in many ways, but it’s an important day because I think it should be a day of decisions.

It’s up to us who loved Tudor’s work to see that it lasts, and that it’s with us for a long time. We talk about Tudor being immortal and he is, of course; that is, he has the possibility of being (so). But we have to keep it that way. We have to keep his works pristine, unblemished, strong, clear, just as he left them, and this is not easy. This is very hard.

Tudor’s work does not depend on pattern, although the patterning is superb. It does not depend on technique, although there is a great deal of very difficult technique. It depends on quality, and quality is a mysterious, even a spiritual word. It’s a combination of attributes; it’s mind and heart, feeling, perception.

Today, dancers are not required to have these things.

Sallie Wilson was just speaking about how Tudor required his dancers to become people. All his performers were people. It didn’t mean that they changed the choreography. He wouldn’t have let that (happen). But they brought to it the entire wealth of their own personalities. Today this is not asked, it’s not even encouraged. In fact, I don’t think it’s always permitted; and, I think it’s pretty damn dull.

The person to do this is, of course, before anyone else is Hugh Laing. He has an infallible memory. He has a beautiful eye. His eye is unmated. His taste is superb and he has the knowledge because he was with Tudor in his creative life since 1931, I think, which is a long-time. Hugh was there, and Hugh helped. Tudor himself has acknowledged Hugh was his critic, his censor, his editor, his spur, and his whip. Hugh knows, and if Hugh can be prevailed upon, and I think he may, this will be an enormous service. The other one is, of course, Sallie Wilson, who has been doing such valiant service up to now keeping the ballets in beautiful order.

But there must be more, and they must train them. I call upon them. I call upon us. Let’s get to work on this very seriously and thoughtfully because this is a treasure. We’ve been blessed to have a real genius; a great, great artist. We’ve known him, we’ve worked with him, we’ve loved him good. We have got to see that his works last.

I went to Ballet Theatre and I saw Dark Elegies; and I was struck (very well done by the way, very well done), and I was struck once more by how astonishing that ballet is. It was created in 1937. Tudor was young. He’d never seen any modern dancing; not Graham of course, not any of the Americans. I don’t think (Mary) Wigman –she had one performance in London and it flopped. There was Kreutzberg, but I never heard Tudor mention (Harald) Kreutzberg. No, no, this came right out of Tudor. It was his feelings for peasants, for earth, for communal, simple expression.

And what is so remarkable here is the beautiful feeling for communal dancing. It’s peasant dancing but there isn’t a single phrase of quoted imitation, not one. It just is suggested in its marvelous patterns. And he has (shown) what’s more the remarkable courtesy of simple people, one for another. You’ll find that all through folk dancing around the world. They are courteous to one another instinctively — the great courtesy of grieving, and suffering for (those) grieving and the suffering. This is what makes this work so very poignant, so heart moving. How did he know that? He certainly never had a child. He never lost a child. How did he know this? Tudor knew. Just as he knew everything he should have.

We were surprised, some of us, when Tudor became a Zen Buddhist. We shouldn’t have been because the seeds of it are in that ballet. Go and look. You’ll see: it’s there. The thoughtfulness, the care for fellow beings, the decorum, the probity, the control, it’s all there.

When we see (Tudor’s) work we get not only a work of art but facets of life itself: wider, larger and we see ourselves larger, more important, bigger, more valuable; the horizon stretched out, and out, and out because he made a statement of absolute truth.

###

Jonas Kåge on the “Magic” of Tudor Ballets

I have experienced Tudor in one way or another throughout my professional life.

My roots are with the Royal Swedish Ballet where Tudor was director in the 60’s and I was a student at the Royal Swedish ballet school. He created Echoing of Trumpets for the Royal Swedish Ballet and staged many of his works for the company. I remember watching performances and have very strong impressions of Echoing of Trumpets, Romeo and Juliet and Pillar of Fire. I was a clean slate and what was written on that slate remains today.

Tudor created Leaves are Fading for ABT in the 70’s with Gelsey (Kirkland) and me being particularly featured. Tudor worked intensely and quickly, comparatively speaking, and was incredibly nervous having not created a new ballet for years. To see him reach deep into himself and pull out what he did was heart rendering for all of us involved.

During my time as Director of Ballet West from 1997-2006, I added several of his ballets to the repertory. I took the opportunity to expose what I feel are important, relevant and challenging ballets for the public and dancers of today.

Ballet West brought an evening of Tudor’s works to the Edinburgh Festival: Leaves, Offenbach in the Underworld, and Lilac Garden. For my last premiere at Ballet West, Echoing of Trumpets was revived, a masterpiece that made a fresh and powerful impression.

Like with all dance works that have become classics, every new generation will discover and appreciate their magic. The characteristics of Tudor’s work and genius would appear quite narrow in today’s dance spectrum, and yet as his prism of works slides into view they shine like strong and bright beacons. The ballets often deal with human relations, conflicts, as well as social issues and will therefore always be relevant – I must add that I am always amazed by the technique required.

Although his works are often psychologically complex, Tudor manages to portray the emotion in a musical score with brilliant simplicity. I find that most of his ballets and his choreographic style have managed to avoid trends and clichés. Or is it that he was completely uninterested and unaffected by trends? I tend to think so.

The strongest validation of his work today is that the young generation of dancers embraces his works wholeheartedly. Perhaps tentatively at first, as the language is, for them, subtle and full of nuances, but as they become fully introduced and begin to perform the works they acquire a new and deeper side to their artistry. These are ballets for thinking and intelligent dancers and for an adult audience. That ballet is an adult art form is often a revelation for many.

That this unusual man would choreograph, what are the chances? And that his works would be so brilliant and have the ability to speak to a wide range of ages, backgrounds and nationalities is in many ways unique. Talk about Dance Theater!

Jonas Kåge

Diana Byer, Artistic Director of New York Theatre Ballet, on Coaching Lilac Garden for American Ballet Theatre:

What could be more exciting than getting a phone call from Kevin McKenzie, Artistic Director of American Ballet Theatre, asking me to assist him in restaging and coaching Antony Tudor’s Lilac Garden. It was a gratifying experience in every way.

What could be more exciting than getting a phone call from Kevin McKenzie, Artistic Director of American Ballet Theatre, asking me to assist him in restaging and coaching Antony Tudor’s Lilac Garden. It was a gratifying experience in every way.

To spark interest in the cast before rehearsals I made a few copies of the 1963 Dance Perspectives two-part series on Tudor as well as a short essay Tudor wrote on Lilac Garden. Once we began rehearsals I also brought in two copies of Stanislavski’s An Actor Prepares for the cast to share.

I realized after the first rehearsal that the challenge for me was how to give the dancers insight into their characters, not just work on the overall shape of the ballet, the steps and spacing. ABT’s dancers are exquisitely talented with strong, clear ballet skill. How would I encourage them to empty their minds of technique and let only the movement enter, what would I do to get them to become their character rather than act it out? Hugh Laing said in Dance Perspectives: “You can’t be a dancer in Tudor ballets. Everything is based on classical technique, but it must look non-existent.” That’s very difficult to achieve.

All of the dancers came into rehearsal already knowing the ballet. I saw a run-through, the first the dancers had done. It was already beautifully rehearsed. After the run-through we sat down together and talked about the story and the characters. I reminded the corps that Tudor never let you feel you were just a member of the corps. You were always an important character and there were no minor roles. I spoke with the dancers about how the guests at the party don’t know it’s a sad story (even though it actually is). They are having a good time. We talked about the need for every dancer to pay particular attention to how they walk and run. We discussed how important it is to remember that the ballet consists of short scenes, all of which take place in the same spot, a garden. So they must walk and run as though they are on grass, very different from how they walk and run in other ballets. We talked about the need to explore how their gestures define their character. We also considered how each dancer at the party is an individual with a separate relationship with Caroline.

Of course, spacing, partnering, movement intention, music and phrasing were all addressed. But we also worked on how to be still and quiet, how the eyes are part of movement, how to make the gestures real, executed in a human way. I mentioned a quote from Karnilova which I found in the April 1982 issue of Ballet News. “Not long ago, [Tudor and I] were talking about how things are today, and I chided him for not doing more. What, I asked, is the difference between now and then?” and he said, “in those days I had people who happened to be dancers, and now I have dancers who are not always people.”

ABT’s dancers were so willing, so interested and interesting, and so respectful of Tudor’s work.

I spent a lot of time rehearsing Melanie Hamrick. This was her first Caroline and because she was replacing another dancer, she had very limited time to prepare.

Melanie immersed herself in Lilac Garden by listening to Chausson’s Poème each night. And we talked each day. About putting aside everything she worked so hard on in other ballets. About not worrying how she looked doing the movement but rather the importance of giving the movement its full value as movement and not as a beautiful looking pose or line. About trying ‘to speak’ as she did the movement, saying something Caroline would say. And about leaving Melanie outside the room and bringing Caroline in, a very hard challenge. She was very brave and courageous as she peeled away the layers of herself to find Caroline’s voice.

I have always found it interesting to stage and coach a ballet on different companies and dancers, especially when it’s Tudor repertory were working on. Each company comes into rehearsal with a different type of training and style, different ways of thinking about what dancing is, and a different sense of how to get their intention across to the audience.

When it all comes together it’s very rewarding. It’s satisfying and special for everyone -the stager, the dancers, the musicians and especially the audience.

Lilac Garden Workshop at Principia College by John Gardner and Amanda McKerrow

This year we spent our holiday season in a quite unique and stimulating way. The day after Christmas we traveled to Principia College for a week long Tudor workshop that was to serve as a pilot program for the official launch of the Antony Tudor curriculum that will take place in June 2011 in Kansas City, Missouri.

The idea for the workshop was put forward to Amanda Mckerrow by the Dance Department Chair at Principia College, Hilary Harper Wlicoxen. Principia had done Little Improvisations a year earlier with much success, and Hilary was hopeful that they could follow up with another Tudor piece. This was to prove challenging due to many factors, most importantly the lack of male dancers. Hilary thought that a good solution would be to excerpt a solo from one of the Tudor ballets. She had a lovely dancer at Principia by the name of Kanoe Wagner who had performed Little Improvisations. Hilary thought Kanoe would make a lovely Caroline from Lilac Garden, and Amanda suggested that the solo she dances to the violin cadenza would be a good choice. Amanda shared this idea with Sally Bliss, and she too agreed that it was right for Kanoe, and it was a wonderful opportunity to bring Tudor back to Principia. However, there were some concerns. One of them being; how does one excerpt a character from a story, and give it the full depth of understanding it requires, if one has never performed the work, or been involved in the process of character development with the choreographer or the cast as a whole? This question opened up much discussion, which led to the idea of a one week Lilac Garden workshop at Principia College. It was important for us to allow this workshop to develop as naturally as possible, and that would mean tailoring some of the specifics to fit the given situation. First of all, the only time we were all available was the week between Christmas and New Years day. While this wasn’t the most ideal time, Hilary thought we could find enough students if she opened it up to community. As it turned out we had fifteen dancers attend, four of them being men, who we were delighted to have, and their contribution was invaluable. The workshop was to include a two hour ballet technique class each day given by John Gardner. Amanda would then work on setting Caroline’s solo and other scenes that are vital to her characterization and the story. The other interdisciplinary classes, Music with Jim Hegarty and Literature with Heidi Snow, added another dimension to the experience, and were certainly informative and helpful. It was wonderful for the students to hear about Trude de Garmo Harper’s personal experiences with Mr. Tudor, which helped bring the man to life. However, it was Meg Eginton’s acting for the dancer classes that really accelerated their character development and enhanced the entire process. Meg attended all of the Lilac Garden rehearsals and designed her classes to directly support what was being done in the studio.

We have always enjoyed working with college and university dancers. Their minds are so focused on learning and they are completely engaged in every aspect of the process. This workshop at Principia was no different in that respect .The dancers all threw themselves into the work with a refreshing curiosity that gained momentum as the week progressed. It was this curiosity of mind that was essential to the success of this workshop in an educational sense, and we found that the more the dancers learned, the more hungry they became to express themselves artistically. We are all thrilled with the outcome of this workshop and truly believe that the Tudor curriculum has the potential to play a most valuable and important role in higher education by providing a tool for the understanding of how to clearly inhabit a given character through dance, and also by teaching the value of being sensitive and mindful of our artistic selves as interpreters and creators of art in the highest. This is the legacy of Tudor, and its continuance insures the integrity and inspiration for the future generations of dancers and choreographers who will explore and carry this art form forward.

We spent time with and met some wonderful and lovely people along the way, and we are thankful for that. We want to especially thank Hilary and Sally for their efforts in making this workshop possible. We want to thank everyone who helped bring this endeavor to life, and that joyfully includes the dancers!

John & Amanda

Kathleen Moore-Tovar: Antony Tudor Reflections

I knew two Mr. Tudors. The first one was the one who chose me to work with Ethan Brown to dance the last pas de deux in Leaves are Fading and to dance the 4th song in Dark Elegies. This man of elegant bearing had eyes that sparkled with wit and mischievousness. Though there was always serious work happening in the studio as he tried to get us to simplify our movement, to dance the steps just as they were, adding nothing, he would tease and joke too. For example, early on in rehearsing Leaves he said to Ethan, “I bet she’s a screamer.” Though my face turned as scarlet as my hair, I replied, “Ethan wouldn’t know.” and Ethan said something to the effect of, “I’d like to find out!” and we all had a laugh. Then we got back to working on making the last embrace in the duet have more of a passionate gasp.

In Dark Elegies, there wasn’t the lightness of mood in the room as during Leaves rehearsals, the dance has too strong a subject, but there was still the constant work on lack of ornament in the body, and always, always, the focus on the music. Another aspect of working with Mr. Tudor was apparent during Elegies, the way he directed us as we toiled on the piece, created in the cast a great sense of community that allowed the work to be the powerful statement that he intended. I am sure his process was intentional; a method used to create individuals deeply invested in the dance and each other so as to better attain the intent of his vision. This ballet remains my favorite work of his that I have danced.

The second Mr. Tudor was the man who picked me out of the corps de ballet to revive the role of Hagar in his masterpiece Pillar of Fire. Almost from the first day this was a torturous period in my career. He sat ram-rod straight at the front of the room, severe and never satisfied. He spoke little, having Sallie Wilson and Hugh Laing do much of the work, which created even more distance from him. He questioned me and never was my answer correct. He would have me spend almost an hour on one step, where again I would fail. I was often reduced to tears that I tried to shed only on my five minute break in a hall closet, refusing to give him the “pleasure” of seeing me cry. Throughout, Michael Owen was my support as well as my character’s support. Again I believe the whole process was intentional; Mr. Tudor tried to make me feel Hagar, find the truth of her with every fiber in my being. To this day, when I hear the Schoenberg music, my stomach tightens in response and I feel insecure and without options (despite the redemptive ending!). Since he died shortly before our premiere, I still wonder if he would have been satisfied with our performances, though I did have the honor of having Oliver Smith come backstage and tell me I had done well… so maybe?

Without a doubt Mr. Tudor positively influenced my approach to all future work I had at ABT and with The White Oak Dance Project. Though times with him were mostly difficult, whether physically or emotionally, I am thankful that I was given the opportunity to work with him relatively early in my career. Since he died when I was only 24 years old, I have fewer memories to remember him by than many others, but two I treasure are these: The first is merely a snapshot, perhaps the first time I saw him up close…he was sitting on one of the simple wooden benches that line the halls on the 2nd floor at ABT’s 890 studios. His hands were loosely clasped in his lap, his spine was erect but not stiff, his chiseled looking bald head was tilted in thought. He radiated the stature, grace and easy command of a high priest. There was power there. My second memory comes from that magical yet nervous time in the theatre…I was on the stage at the Metropolitan Opera House around 6:15 pm, with the big, golden, silk curtain open and house lights illuminating the red velvet chairs so soon to be full of a discriminating audience. With my hair slicked back into a sleek low bun for my upcoming premiere of Leaves but with no stage makeup on yet, I was going through every moment of the piece, my blood full of butterflies. Mr. Tudor quietly crossed from downstage left to right, looking straight ahead. At quarter, before his exit, he turned slightly towards me, ran his hand across his head as if running it through his hair, and with a slight smile he said, “Looking like me tonight?” and then he continued on.

Nancy Zeckendorf: Eulogy For Antony Tudor, 1987

Back row (L-R) Anthony Bliss, Sally Brayley Bliss, Rev. Grant Spalding, Seated: Antony Tudor, Mrs. "Kick" Erlanger holding Mark B. Bliss, Nancy Zeckendorf (Right) at Godson's Christening in 1968

Nancy Zeckendorf: Dancer, Dear Tudor Friend and Philanthropist, Presenting her Eulogy for Antony Tudor:

I first met Tudor at Juilliard and studied with him there and at the old Met. He was then Director of The Met Opera Ballet, where we also worked together. He was my teacher, my favorite choreographer, my mentor, my inspiration, my conscience, but he was also my friend; and, in our later years a mutual trust seemed to have allowed me the role of go between and helper.

Last August I received a letter from Tudor asking me to accompany him to The Kennedy Center for the Honors Award. He went on in the letter to lament “even I will probably have to go through the tortures of a black tie, and probably tight shoes; and it will play hell with my old man routine.”

But he dutifully went out to Syms and purchased the most elegant tuxedo. He hadn’t worn one in years and he even managed to find a pair of comfortable shoes. He wanted to take the trip by train and so we boarded Amtrak with a bag of freshly baked bran muffins for his special diet. He polished off a few of these and then proceeded to eat anything and everything in sight for the next three days. He even ordered a martini for lunch on the big day. And I eyed him warily. After all, I was supposed to take care of him; but he was fine and rejected the idea of a nap in favor of a trip to his favorite museum, The Freer, to pick up his Japanese postcards he loved so much.

Every time we left the hotel during those three days he was surrounded by friendly faces asking him to please sign their books, or could they take his picture. He was really quite surprised and rather pleased. I don’t think that happened much in his life.

The night of the awards presentation at the Kennedy Center was the most moving, enthralling experience of my life. The moment for Tudor finally came. Agnes DeMille brought down the house with her speech and Margot Fonteyn brought us all to tears when she said, “It is very fitting that he should receive this most prestigious Kennedy Center Honor because his extraordinary talent has enriched the whole art of dancing.”

She held out her hand to Tudor, “Dear Antony, we the dancers and the public salute you and thank you for all you’ve given us.” There were tears in Tudor’s eyes as he gave Margot and all of us his Buddha bow.

It was the proudest moment of my life to have been there to see him so warmly and wonderfully applauded and cheered by that remarkable audience. I know I speak for all of us here when I say it was an honor to be a part of his life.